This tech “recession” is almost entirely about investor sentiment

Strange times in tech-land these days. If you’re reading this blog, you probably know about this:

But have you also noticed… uh… this?

It’s a funny sort of “recession” when the economy continues to grow robustly, the Fed is hiking rates specifically because demand remains too resilient for their liking, and tech companies are more or less hitting their (admittedly cautious) projections.

And yet, people are losing their jobs, and the frightening justifications they’re hearing for it are “economic turmoil,” “market turbulence,” and “bad macro”. Hopefully in this post I can clear up a little bit about what that really means.

Business performance is only one consideration out of many

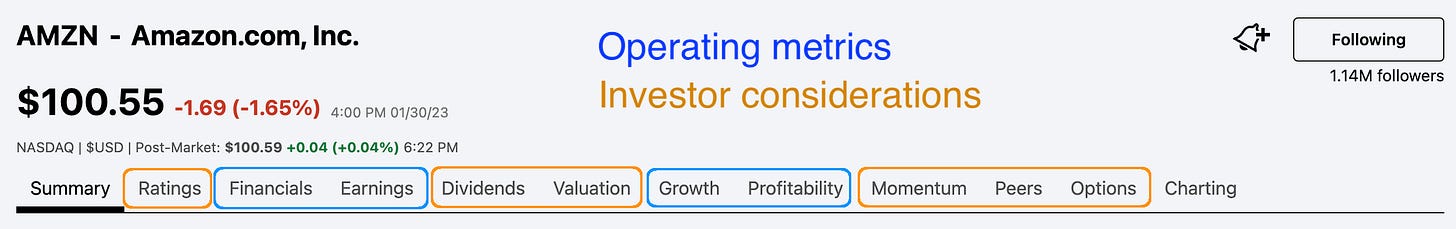

If you go onto a stock tracking platform like Seeking Alpha you’ll see a whole bunch of tabs that analyze various important considerations to the company’s stock price. Something like this:

One thing you might notice by flipping through these tabs is that only some of them have to do with the actual fundamental performance of the business. A good chunk of them are instead related to the interests of the investors, namely: What they think of the stock, how much they expect to be paid for holding it, how the valuation has changed recently, how this performance relates to peer companies, and so forth. Stuff that is mostly separate from how the business is actually doing.

The point I’m making here may or may not be obvious — business performance is important, but lots of external factors also go into whether a company and its prospects are perceived as “good” or “bad”.

Why the “climate” is important

One question you may have asked yourself is why VCs are so preoccupied with what their peers are thinking and feeling. The answer is that they need each other’s money.

Imagine that a VC leads a Series A round of funding into a tech startup. In almost every case, this company will eventually require more capital from somewhere to continue on its growth trajectory. And this is especially true when the company is more successful or promising, because there’s a higher justification to spend money to grow faster.

While it’s true that not all tech startups require gobs of new money to continue growing, and that sometimes the same investing syndicate will provide more capital to get the business to break-even, in practice “more capital from somewhere” usually means “from someone besides us.” Which means that market perception is really important for investors and operators, even those with the most “heads-down” posture.

(This is also why VCs tend to “play nice” with their peers, more so than private equity / buyout style investors, at least usually.)

Why are my VCs giving me a hard time about burn, when twelve months ago they told me to hire as fast as possible?

Sure, let me expl—

No, seriously. What is wrong with you people?

Let’s linger on the “more capital from someone besides us” part for a minute. Whether that capital is cheap or expensive then becomes a hugely important consideration.

To illustrate the point, we’ll come back to the Series A investor example. Imagine a maximally terrible capital market where other entities will only fund this investor’s portfolio companies at pre-money valuations of one dollar. In that universe, every cash-burning company is worthless because any new financings dilute the cap table to nothing, preventing the possibility of returns for everyone. Which means that the Series A investor’s portfolio in this universe is worth zero.

Now imagine the opposite universe — all startups regardless of stage or traction are now worth $1 billion dollars pre-money (this is sort of like what happened in 2021). This is awesome for the Series A investor’s portfolio because all of his or her companies essentially get free money to continue growing fast, at nearly zero dilution to the existing investors. Which makes their shares worth a lot more!

It’s tempting to say that peer VCs only matter in the context of “marking each other’s companies up,” i.e. providing short-term superficial validation to help the investor get promoted and/or raise new funds. But the truth is that market exuberance or lack thereof legitimately drives enterprise value and returns potential. That’s why they really, really care about it. And that’s why investors often steer their companies towards doing whatever the prevailing investor appetite demands, whether that’s growth, or profitability, or whatever.

Recently, for lots of reasons beyond the scope of this post (but which essentially come down to war, inflation, China, reversion to the mean, and most importantly the observation that their peers are feeling the exact same way), technology investor sentiment has shifted from “maximum exuberance” to “maximum fear.” This, more precisely than any one of those factors individually, is what’s causing capital to dry up, and every company to downshift hard from offense to defense.

Unfortunately, we live in a dynamic world, not a static one.

Dislocations between what the market demands companies optimize for now, and what the market will demand next year once those decisions are implemented, cause a lot of turmoil in startups and growth companies. And if you add in the recursive feedback loop between valuations and sentiment (“valuations are low, which makes me want to stop investing, which makes valuations go even lower”), you get a super unstable system with wild swings upwards and downwards.

Which is how you get situations like this:

None of this is to say that some companies aren’t really struggling, or that recent layoffs are unjustifiable. I just think that some business leaders on both sides of the table are explaining the current moment to their teams in ways that are imprecise and confusing. And frankly a bit irresponsible.

Please don’t scare people into panicking about a phantom recession. Blame the money people, but don’t blame the economy.