The absolute best place to be in SMB software

You may have heard that 99% of businesses are small businesses. If you’re involved in the B2B software ecosystem like I am, the thought may have occurred to you that providing modern digital tooling to “the long tail” of SMB businesses is an enormous business opportunity. Huge markets and quick sales cycles (often with only one decision-maker to close), what’s not to like?

Well, it turns out there’s a big “but”, and that “but” is called Price Point. Small businesses have significantly less money available to pay for your software. Let’s decompose why this is a problem:

Obviously, cheaper software requires a lot more customers to generate the same ARR as expensive enterprise software, so you need end markets with lots of n-count of buyers, ideally ones with some level of horizontal aggregation (e.g. you can sell into the corporate office of an entity that owns a few dozen restaurants, salons, gas stations, etc. and knock down new business in chunks).

Lower price point requires a correspondingly low cost of acquisition, which forces you to be increasingly clever in your sales motion.

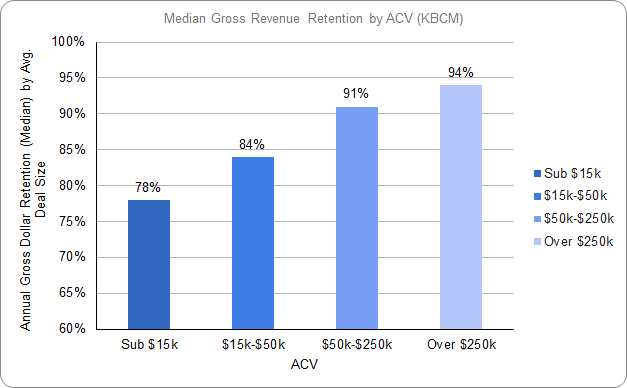

Perhaps the most insidious issue is that gross retention is positively correlated with price point. Meaning that smaller contracts churn at higher rates, see below:

This is sort of counterintuitive because it flies in the face of basic notions of demand elasticity (shouldn’t customers be less willing to continue paying for something that is more expensive?). There’s actually two things happening here to drive this:

Larger customers (the kind that spend 6-figures and above for application software) have larger discretionary budgets in general, and so by selling larger contracts you are selecting for higher willingness to pay in general. If they’re bigger, they also have the higher potential to experience ROI from buying technology.

Sunk cost psychology is also at play… if you invested $100k into a piece of technology you’ll be more likely to enforce usage and try hard to make it work. Whereas it’s much easier to completely forget about some widget you’re spending $29/mo on.

Interestingly we see the same effect with onboarding/setup fees and annual pre-pay contracts — customers that pay more upfront are much more likely to renew. And of course, SMBs are much more reluctant to pay significant setup fees or pay for a year of service upfront (though it’s not unheard of). So when we talk about the challenge of low price points in SMB, we’re not just talking about the nominal subscription fee; it’s inclusive of all cash outlays that customers make for technology.

As you probably know, it’s almost impossible to scale a SaaS company that doesn’t have good retention.

If you want to win in SMB SaaS, you need to solve the price point problem

The only1 way I know to unlock all the benefits of selling into SMB without getting eaten alive by churn and CAC is to achieve and defend higher ACVs.

You might be sensing a contradiction here — aren’t SMB products definitionally sold at lower price points? Yes, but not all small businesses are made equal: Some are larger, more profitable, in spendier geographies, and/or are run by (often younger) managers and owners who understand the value of technology. Some examples:

A hair stylist who wants to handle online bookings might pay $29 per month for Booksy, but a high end salon will pay $300+ per month for a sophisticated business management system like Boulevard. (note: Toba portfolio company)

A typical main street retailer or restaurant might be content to do invoicing or accounts payable by hand, but a business that optimizes for its managers’ time efficiency might have no issue paying $79 per user per month for Bill.com.

A family restaurant operating at near-zero margins might see no sense in paying commission fees to DoorDash, whereas a high volume QSR in a ritzy part of town might find it absolutely necessary to stay competitive.

If a SaaS vendor can find a clever way to command higher ACVs and sell itself into a more upmarket customer segment, they can obtain all of the advantages of selling into SMB while also having the retention and unit economics characteristics that enterprise software companies enjoy. This is the Holy Grail.

How does one accomplish this? I’m not saying it’s easy — it requires a legit moat, tons of product work upfront, and clever segmentation. I wrote about this at length in this pre-Pandemic post but to summarize, here are the typical ways I’ve seen that work:

Marketing specifically to a premium/luxury subsegment within your target market

Expand your product scope to include things like payment processing or marketplace booking revenue

Offering white-glove support and onboarding, and charging a lot for it

Becoming known as the vendor in your space with the best integrations to other SMB products like Quickbooks

Being able to sell growth or revenue as a value prop, not just savings or efficiency

Dominating a vertical and becoming known as the gold standard in that profession, perhaps by seeking endorsements from the key trade associations in your vertical

If your customer base will tolerate it, mandating annual commitments

[Takes a deep breath] Being the first vendor in your space to come up with a legitimately strong use case for AI

It’s trite for a venture capital investor to suggest that you merely build the best product and charge the most for it… but I really think that is the main trick in SMB. Or at least it’s what I’ve seen work best in our portfolio. Other software categories seem to lend themselves better to undercutting incumbents from below, but in SMB having the most expansive and premium product often is the winning move.

Thanks for reading. If you’re building a company that is attempting to attack its market in the method I described below, please do reach out.

Without pivoting into a marketplace business or a data broker business, which can also work but for very different reasons than SaaS.