I've been crowing for (checks notes) uh, eight years now, about my worry that the rise of standardized metrics and a "playbook" for the SaaS industry is going to drive down experimentation -- and eventually returns:

What are the lean startup model, standard SaaS reporting templates, endless blog literature, and so on if not ways of adding more predictability to the startup creation model? (more on this here, if you have the time: Entrepreneurs Are The New Labor: Part I). And with increased predictability comes decreased risks, with which come lower returns. Venture becomes just another asset class (well, it already is, really) with a relatively unremarkable risk/return profile; a far cry from the days of "mavericks, innovators, and crusaders heralding a bright new future through free enterprise" (compare the Ford Motor Company in 1910 to the Ford Motor Company in 2015). Additionally, with the explosion of entrepreneurship and new startups created, the pace of new company formation is likely outpacing the ability for the market to bear new successful companies. Put another way -- sure, the technological frontier is advancing at an exponential rate, but the number of new startups is probably growing at a far greater exponential rate. That, when combined with competition between startups duking it out over new categories that will probably only end up supporting 2-3 mature companies by the end of it, means a lot of dead startup carcasses.

The fact that I wrote something that sensible-sounding in my 27th year of living is a minor miracle. But anyway. Here's the thesis in a nutshell:

Startups take advantage of the fact that the future is uncertain.

Uncertainty is a barrier to entry because taking on risk is scary, especially when you have lucrative alternatives like a six figure job at a stable, reputable firm.

The more an industry is de-mystified, and the more the playbook for success is codified, uncertainty decreases and supply of new entrants increases. For example, Y Combinator made it easier to explain to your parents that you're founding a startup instead of taking a job at Bain, and now there's about 600 new YC companies every year mostly founded by people in their twenties.

Less need to experiment means less "winging it", or tinkering with business processes, which means a narrower dispersion of outcomes. There are less complete disasters, but also less breakout winners that nobody saw coming.

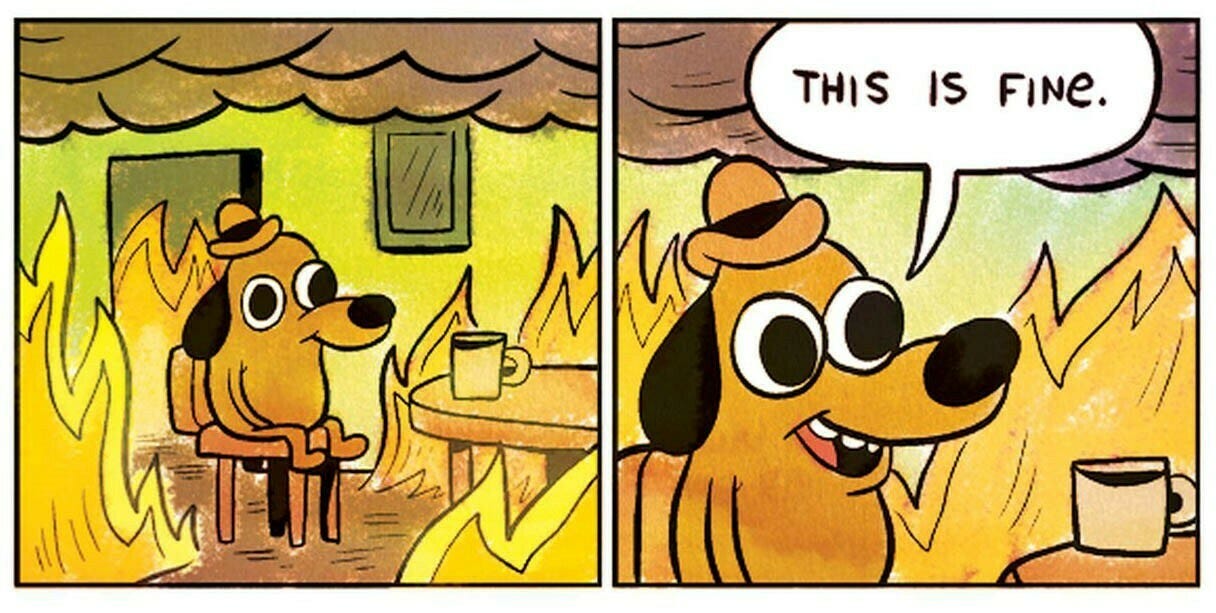

The last decade of the SaaS industry has borne this out, I think. One big thing I've noticed since Jason Lemkin gave us all SaaStr and its thousands of articles of tactics for building a cloud software business, is that a much higher proportion of SaaS startups are just.... fine. They're growing at a fine pace, they have a fine product, retention is fine, unit economics are fine, company culture is fine.

Not only are they fine, but everybody is a whole lot smarter about the standard approaches for managing them. When David Skok came out with his seminal SaaS Metrics article (in 2009, I think?), a lot of this stuff was not widely known. Now it seems inconceivable that a software CEO wouldn't know at least 2/3rds of these metrics and ratios by heart.

Fine is good! Better to be fine than to be a disaster with no hope of getting anything off the ground.

But with the rise of "fine" SaaS startups has come a lot less diversity of company-building techniques and overall just a lot less weirdness -- both the good and bad kind of weirdness. Bad weirdness is when you were ignorant of industry-standard processes and instead "winged it" to your detriment. Good weirdness is when you did the exact same thing, except the bespoke process you conceived for your company turns out to be a lot more interesting than whatever the prevailing dogma was. Turns out that if you spend more time deferring to the standard startup playbook, you reduce both sorts of weirdness from your company.

As a personal example, I have one friend who followed a Four Steps to the Epiphany-like customer/product development procedure to develop his SaaS startup. And it went... fine? I think he will do fine! But it's weird, I can't help but read his investor updates and feel that the whole thing is just a tad paint-by-numbers. He's making one highly sensible business decision after another, and I can't criticize any of them individually, but they all add up to a business that seems unlikely to break out as a result of decisions they're making about how to structure their company & processes. Now I can't begrudge him for it -- he has children to feed, and I want him to do well -- but part of me wishes for him to have a much grander and more uncertain adventure than the one he currently appears to be on.

If you look at most startups' websites these days, you'll see similar to this: most look highly reputable and pretty polished. Far from being non-consensus and right or a good idea that sounds like a bad idea, a whole lot of SaaS companies these days are pretty consensus good-sounding ideas that also happen to be right. That's great for consumers of software but might indicate some industry commoditization or perhaps startup oversupply.

As an investor who seeks to utilize the power law to drive outsized returns from outliers, this really concerns me. I cannot do well investing in companies that are merely "fine" when entry valuations are priced to perfection. I need explosive growers at entry prices that reflect some uncertainty or lack of consensus about the trajectory of the business. How am I going to find that when everybody now believes in SaaS, the glidepath of this type of company is extraordinarily more predictable than it was a decade ago, and the degree to which they are "weird" (read: have innovated on some attribute that turns out to be really important) has gone down and down and down? I don't know.

SaaS : 2015 :: Vertical SaaS : 2023?

Matt Harney found a fun little list of vertical SaaS investor theses put together by Nick Tippmann earlier this year. It's really good! I've been having a lot of fun paging through them, and I agree with tons of what they are arguing. But I also noticed that the sheer number of these investor theses has been exploding. Yes, this is an unscientific sample. But look at the proliferation:

Pre-2021: 5

2021: 5

2022: 17

2023: 10 as of April, so on pace for 30 by end of year if the list kept updating

On one hand -- yes! Great reading material for all of the vertical SaaS founders in the Toba portfolio. But on the other hand... is vertical SaaS now consensus? Are there really, really good playbooks available that founders would have killed for a decade ago? Are there very high profile public vertical SaaS companies out there trading at high multiples? Are there new accelerators and other onramps that exist to de-risk entry into the category? Now I'm getting a little worried about where I'm going to find alpha in an environment like this.

I'm absolutely not abandoning SaaS or vertical SaaS anytime soon, but I'm starting to get a bit nervous. I just want startups to be a big journey into the unknown, the way it seemed when I took my first tech job in 2008. I want to live on the bleeding edge, where there is no playbook. And I want to do that while being mindful of the fact that no one is easier to trick about what's coming next than a venture investor.